Reporting and photography by Madi Koesler

For Street Sense Media – original article linked here.

Printed in Feb. 26, 2025 edition.

As public space grows increasingly rare in the District, encampment engagements significantly increased in 2024, displacing over 100 people, based on Street Sense’s reporting.

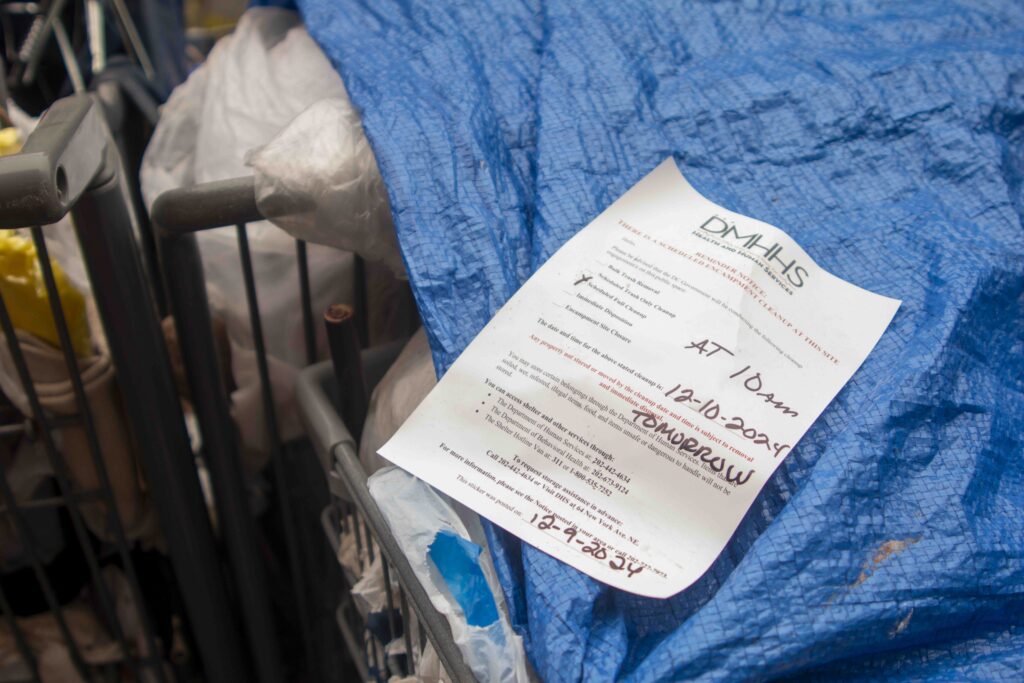

Encampment residents consistently voice anxiety surrounding site closures and continuous relocation. A lack of accessible information adds to this anxiety. Signage placed in advance at engagements, the contours of which can vary widely, does not say what residents can expect the day of.

The 2019 Encampment Protocol defines one primary category of engagements: “standard dispositions.” When conducting standard dispositions, the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services (DMHHS), which houses the encampment team, gives residents 14 days’ notice before cleaning the area and removing any belongings, according to the protocol.

In practice, however, DMHHS more commonly uses the terms encampment site closure, full cleanup, and trash-only or bulk trash removal actions. These terms are unmentioned in the 2019 protocol but can be found on the yearly engagement summary documents DMHHS publishes. Closure, while not expressly defined in the protocol, is typically used by DMHHS to designate encampments where residents cannot return to the location after an engagement.

As part of D.C. Council oversight hearings, DMHHS recently outlined additional guidelines regarding these terms. These guidelines provide some details on how trash and hazardous materials are removed during cleanup engagements, saying DMHHS works with D.C.’s Department of Human Services, the biohazard team, and D.C.’s Department of Public Works to remove bulk trash, hazardous materials, and remaining items. But what these protocols look like varies. Part of this is because the size of encampments can range from one shopping cart to multiple tents. Based on engagements Street Sense has attended, the larger an encampment is, the more likely DMHHS is to contract more workers or equipment.

Because engagements aren’t standardized, it can be difficult for residents to know what to expect until the day of the cleanup. Oftentimes the job of explaining what clean-ups and closures are falls onto the backs of outreach workers.

“If the goal is we need to complete this work, this type of city maintenance work, at this site — would it not be in the best interest of that goal to have everyone that is living there understand as much as possible what is happening that day and why?” Abigail McNaughton, an encampment case manager at Miriam’s Kitchen, said.

McNaughton and residents said the lack of definitions on signage leads to confusion. Residents aren’t always aware when they are allowed to move back to spaces, and described the process as a “cat and mouse game.”

During clean-ups, the culture among government officials is consistent. Street Sense witnessed officials operate heavy machinery while smoking cigars and cigarettes, kick and throw items into piles, and crack jokes.

Last year, DMHHS initiated 62 “full cleanups,” fully closing 32 of these encampments. This is a 77% increase from the 35 “full cleanups” in 2023.

But this increase doesn’t correspond with equivalent increases in housing opportunities like vouchers and shelter beds. Residents describe this lack of options as a feeling of “oppression.”

“DMHHS has been weaponized to erase the proof of homelessness, targeting encampments and throwing away what is, oftentimes, every item an individual owns,” Joshua Drumming from the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless said during a recent DMHHS oversight hearing.

DMHHS’ bulk trash removal ranges from removing trees and tents with heavy machinery to offering residents trash bags, based on clean-ups Street Sense has attended.

While DMHHS removes items, many clean-ups don’t consist of thorough cleaning. Street Sense reporters have witnessed items such as food trash, condom wrappers, cardboard signs, and bars of soap left behind.

Biohazard engineer Virgil Martin typically sprays Spic and Span and removes health hazards, but the space isn’t necessarily prepared for public use.

Damage to surrounding nature is also common when heavy machinery is involved. During some of their 2024 cleanups, DMHHS removed small trees and foliage using Cat 299D3 Compact Track Loaders, including at the Oct. 3 closure at 1280 Union St. NE.

When clean-ups accompany closures, the main difference in protocol is the restriction of the space after the cleanup. Sometimes additional signage, locks, or fences are added with the help of the District Department of Transportation. Residents typically return to encampment spaces after cleanups when sites aren’t closed, which DMHHS is aware of.